by PAIREDProject | Sep 22, 2023 | Pain

By Jessica Robinson-Papp

One of our PAIRED project research studies, called TOWER, studied how best to implement the CDCs opioid prescribing guidelines in the HIV primary care clinic. We started the study because when the original guidelines came out back in 2016 we worried that they might make life difficult for patients living with chronic pain who depended on opioids. We ran the study in the Institute for Advanced Medicine, a primary care network at Mount Sinai that serves a large population of people with HIV. As the project progressed, I gained real-world experience assisting primary care providers navigate these challenging patient encounters, and came to be regarded as the local opioid management expert.

With passing years, opioid management has only become more complex. In 2022 there was a settlement of litigation brought by 46 US state attorneys general against the distributors who supply opioids to most of the pharmacies across the US. Part of the settlement mandated that the distributors implement “controlled substance monitoring programs (CSMP).” My first awareness of a CSMP came in the form of a call from a pharmacist who told me that he couldn’t fill one of my patient’s prescriptions because he had reached a “threshold” imposed by the distributor. The distributor had specifically singled out my patient because of her high dose and told him to contact me. As many physicians might, I reflexively bristled at the questioning of my judgment. Then I worried about the physical and mental impact a sudden loss of opioid access would have on my patient, and then I felt my heart sinking in anticipation of the time and energy that would be required to coordinate her care. And what if this were a harbinger? We would quickly be overwhelmed by patients in opioid withdrawal. On the other hand, I also felt some relief.

When I inherit a patient on opioids for chronic pain I try to manage their care like we did in the TOWER study. The crux of this approach is weighing risk and benefit. We all know the risks, but what do the data tell us about the potential benefits of opioids? There is good evidence that opioids help pain in the short term, but it’s not so clear for the long term. You can’t run clinical trials for years, and even if you could we don’t even agree on the outcome we should be measuring… pain relief, function, quality of life, treatment satisfaction or something else. The choice is important because these outcomes don’t always go hand in hand. For example, a 2006 study concluded that strong opioids improved pain but not function, while weak opioids and non-opioids improved function but not pain. More recently, one study found a small but significant benefit of opioids on health related quality of life, but with the caveat that the data were based on a relatively short average treatment time of 15 weeks. Open, non-randomized trials suggest pain relief with long-term opioid use, but epidemiologic data are generally less positive. For example, a large population-based study in Denmark demonstrated that patients receiving opioids long term had poorer outcomes than those who did not receive opioids. Also injured persons treated with opioids are less likely to return to work. However, these studies are confounded by the fact that in clinical practice there are important differences between patients who remain on opioids long-term and those that do not; with the former having higher prevalence of substance use and psychiatric diagnoses.

Using these complex data to weigh opioid risk and benefit for an individual patient is imprecise at best. Still I have to figure out how to treat the patient in front of me, and that’s the hard part, even though there are only three options: continue the opioid at the same dose, taper, or stop prescribing. I have to judge which option has the best risk benefit ratio, and not just for the patient. Given the risks of diversion, I must also judge the patient as an opioid steward. Will they effectively prevent the opioid from being used by others? This passing of judgement is unusual in the practice of medicine, and its finality may be unique. I know that if I don’t write the prescription it is highly unlikely in the current climate that the patient will find someone else to do it. And so that whisper of relief I felt when hearing about the CSMP for the first time came from the prospect of being relieved of the responsibility of judgment. Of course I wouldn’t actually want it to happen, and I accept my responsibility, but I do miss the simplicity and satisfaction of being my patients’ uncomplicated ally.

by PAIREDProject | Jun 9, 2023 | Clinical trials, Pain

By Jessica Robinson-Papp, MD MS

By Jessica Robinson-Papp, MD MS

Every Thursday afternoon, I meet with my collaborator and friend, Dr. Monica Rivera Mindt. Dr. Monica Rivera Mindt. Dr. Rivera Mindt is a community engaged researcher who has spent decades living and working in the Harlem neighborhood of New York City focusing on brain health, specifically the mechanisms underlying racial and ethnic disparities in cognitive decline. Last week we got to talking about the different ways we have engaged with communities and how successful it has been in supporting many of our studies, particularly those focused on brain health. Today it’s the norm to include people with lived experience in the design, execution, and reporting of all kinds of clinical research. But like many things that we start to take for granted, if we don’t periodically stop to reflect on why we do something, we risk losing purpose and authenticity. Following our conversation, I wanted to remind myself of the fundamental reasons for community engagement in research. Why do we think it’s a good idea and what do we know about its effects on outcomes? I also wanted to think more specifically about community engagement in the context of pain research. So I indulged myself in little reading.

I found a comprehensive chapter on ResearchGate (published in 2008) describing the evolution of Community Based Participatory Research (CBPR) titled: “The theoretical, historical, and practice roots of CBPR,” by Bonnie Duran DrPH of the University of Washington in Seattle. Dr. Duran traces the history of CBPR back to the 1940s when the term “action research” was coined to describe a self-reflective and collaborative quality improvement method. She also draws a lineage to CBPR from the social justice movements of the 1960s and 1970s which sought to reduce inequities between researchers and study participants, including providing greater access to and control over study results and their dissemination. This historical context suggests that diverse stakeholders were originally included in research both for their unique insights and also for ethical reasons.

Many years later, patient-engaged research got a boost from the Affordable Care Act (aka Obamacare) which led to the establishment of the Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute (PCORI) in 2010. PCORI’s mission is to “fund research that helps people make better-informed healthcare decisions based on their needs and preferences.” As a funder of research, PCORI is unique in that it requires researchers to include patient input in their research process. This was still pretty novel at the time of PCORI’s founding; a Pubmed search of the term “patient engagement” shows a inflection point right around 2010 with increasing numbers of publications in years since. Requiring patient input for studies of healthcare delivery, such as those funded by PCORI, seem like common sense. If your goal is to help a group of patients make informed choices it seems obvious that you’d need to involve those very people in your study design. But it would still be nice to prove that patient engagement improves these studies. PCORI set out to do just that in an article published in 2019. Since all PCORI studies require patient engagement, a formal comparison of studies with and without patient engagement wasn’t possible. Instead, the authors reviewed 126 articles describing PCORI-funded research and performed a qualitative analysis of text pertaining to patient engagement. They concluded that “…findings suggest that engagement contributes to research that is better aligned with patients’ and clinicians’ needs.” This is encouraging, although a cynic might wonder about the likelihood of PCORI-funded researchers including negative statements about patient engagement in their publications.

So too in the field of pain research has patient engagement become a popular idea. The International Association for the Study of Pain (IASP) published a fact sheet on the topic last year. The Helping to End Addition Long Term (HEAL) initiative, the body within the National Institutes of Health (NIH) that funds pain research has also emphasized the importance of patient engagement. But does it really make sense to seek the patient perspective in all forms of pain research?

It feels slightly scandalous to suggest, but is it possible that patient engagement has gone too far, and that by extending it past its original purpose we are diluting its power? This question may be particularly relevant to tightly regulated areas of research, such as early drug development, in which study design may be mostly dictated by budgetary limitations and the requirements of regulatory bodies such as the Food and Drug Administration (FDA). The needs of patients must still guide such research, but what if the perspective of the clinician-scientist on these needs is enough? Clinicians interact extensively with patients absorbing their perspectives over hundreds and thousands of encounters. This is effectively qualitative research, albeit informal. The idea of the clinician as patient proxy is unpleasant, it sounds authoritative and paternalistic. But is the engagement of a handful of people with lived experience really likely to be less biased, or is it just something that’s become accepted as a “best practice” without strong rationale? If it’s the latter, we should be brave and acknowledge own our own expertise as clinician-scientists, while respecting the time and wisdom of community members by engaging with them only when their input really matters and when we can engage whole-heartedly.

It’s quite likely that there will never be strong quantitative evidence that patient engagement improves research. That doesn’t mean we shouldn’t do it, rather we should strive to engage patients in research areas where common sense and the historical origins of CBPR indicate it’s important, particularly research involving ethical and/or value-based decisions.

by PAIREDProject | May 25, 2023 | Clinical trials, Pain

By Mary Catherine George, PhD

By Mary Catherine George, PhD

The eternal question my family and friends ask me is, “Why are you involved in scientific research for pain treatments?” My first career was as a professional opera singer. My journey into scientific research was accidental. I loved singing, yet suddenly, I had no job with the opera company that hired me. My brother worked at St. Vincent’s Hospital in “the Village” in New York City; he suggested I talk to the doctor he was working with because they needed help in their research program. I needed a job, so the doctor showed me a file drawer full of paper. It didn’t seem scary, so I said yes. Little did I know my experience working in research during the HIV/AIDS epidemic would teach me a profound lesson – the power of research. I witnessed so many people diagnosed with HIV/AIDS, with limited choices or prospects for survival, they would show up for the few research studies available. All with the hope for a possible treatment.

Dr. George as the Countess in the Marriage of Figaro

Dr. George as the Countess in the Marriage of Figaro

Thankfully, HIV/AIDS is no longer a death sentence; because of successful research studies, treatments were developed and continue to be developed. Eventually, I transitioned my work to the Mount Sinai Health System. I became curious about how individuals who suffer with chronic pain can have the same medical problem but have a different pain experience. Every patient had a unique view of how they experienced their pain. Pain is a complex condition, and many factors, such as environment, culture, disease, personality, and life experiences, can influence how each of us experience pain. I decided to return to school and get a doctoral degree in Health Psychology because I wanted to help understand more about the elements that play a role in how we experience pain and well-being.

I am now in the process of working to develop a technological treatment for chronic pain. I am still at the beginning, yet engaging in research offers an opportunity to learn, discover, and advance what we know. It is how to help all those who suffer daily from chronic pain. Research can often be complex because we must show how something works and demonstrate safety, which means working closely with research participants doing a lot of tests during several study visits. Many patients would prefer not to participate in a research project, because the drug or device is not approved by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA). Yet, sometimes the opportunity to understand how we experience our health and pain can come from a different, unexpected direction. That is what research has taught me.

Living with chronic pain can often feel as if we are under a magnifying glass because the feelings of discomfort are so oversized. Exploring or seeing or thinking about chronic pain from a unique new perspective can change that experience. During recovery from my hip replacement, I used a brief mindfulness technique that I was taught in a research study. The idea of exploration outside of what I previously knew helped my health and well-being.

Curiosity can be a viewpoint that offers new insights into our human experience. Pain is something we all experience as humans. Is it any wonder it sparks my curiosity? Finding better treatments and offering ways to reduce pain can help so many people. No matter how difficult it is to make new treatments, scientific researchers are inspired to continue working hard to find medicines that will help. I am excited that I am part of this group of researchers. We cannot do this alone. We can only develop new therapies as a community. I know the important lesson I learned was persistence, because what I witnessed in the early part of my research career taught me to keep trying. The heart of research for me is being surrounded by a team whose members all want to improve the lives of those who suffer with chronic pain.

by PAIREDProject | May 19, 2023 | Clinical trials, Pain

The last several years have been an exciting time for pain research, as the tragedy of the U.S. opioid epidemic funneled attention and resources toward efforts to find new, non-addictive pain treatments. We’ve all seen the numbers, millions and millions of Americans with chronic pain, and few if any safe and effective treatments. There’s an old observation among researchers that common diseases are common until you try to study them, then suddenly there are no patients to be found.

At the PAIRED Project we’re part of a nationwide consortium for pain clinical trials called EPPIC-Net and recruiting patients to be in our first two clinical trials, one for knee osteoarthritis and one for diabetic peripheral neuropathy, has been a challenge. But like any challenge it’s also an opportunity to learn and we’ve been thinking a lot about why this has been so hard and how we can do better.

For our HIV-focused studies, like EVA and SALUD, recruitment has been much easier. Maybe understanding why would help us with our pain studies. Well first of all, it’s a different disease. HIV has a moving history that’s inspired books, movies, and musicals. It also has a legacy of vibrant and persistent advocacy. On World AIDS Day last year, when members of our team joined VOCAL-NY activists near the Stonewall National Monument, a chant broke out: “When people with AIDS are under attack, what do we do… Standup, fight back!” For many people living with HIV, the HIV is a part of their identity. There are a lot of conditions like that, they’re usually the ones that have associations, walks, challenges, ribbons, recognizable abbreviations (like MS, ALS), maybe a celebrity or two. These same conditions also tend to have medical homes, clinics devoted to the care of those patients’ specific needs. Since the beginning of our careers we have been a part of meeting these needs for people living with HIV. Dr George is our veteran, she was even there for the first HIV treatment trials. So when a new HIV study comes up, it’s easier to ask the community to participate when there’s a history of trust built over time.

But what if there’s less history, and less of a clearly identifiable community? Chronic pain isn’t a single, defined disease like HIV. It hasn’t been a rallying cry or a reason to march. It’s an experience common to many disorders, including the ones we’re trying to study, knee osteoarthritis and diabetic peripheral neuropathy, but also many others. From a drug development perspective, especially in the early stages, it makes a lot of sense to think of chronic pain disorders in aggregate because their treatments tend to overlap, a drug that works for diabetic peripheral neuropathy pain is likely to also work for fibromyalgia. But drug development requires people to participate in clinical trials, and from a recruitment perspective chronic pain as a disease focus is very tricky.

Why? Well, recruitment to any research study can be thought of as the process of finding interested and eligible patients. Eligibility is pretty straightforward and controllable. The researcher writes the inclusion and exclusion criteria for the study and could always change them if they are too strict. Many research studies are conducted in large health systems with electronic health records that (with appropriate privacy protections in place) could be programmed to produce lists of patients that meet a set of criteria.

Interest, however, is much more complicated. Why might a person want to participate in a clinical trial? Maybe they want access to a new experimental drug that they couldn’t get otherwise. For very serious or potentially fatal diseases (cancer, ALS) access makes sense as the main driver. But what about when your life is not in immediate danger from your disease, what if instead you are long suffering neither better nor worse from month to month, from year to year. Why participate in a study, especially now when the energetic barrier to get out and participate in anything seems so much higher than it did before?

As a pain research community we desperately need good answers to this question. Chronic pain needs a story that inspires books, movies, and musicals. It needs to go viral. Then we and our research participants could be characters in the narrative of how this terrible condition was ultimately conquered. The story of chronic pain can be compelling, but it requires creativity to tell well. Perhaps it is a story of how a universal experience that is one of our most basic defense mechanisms, something we all need to survive, can turn on us… a story of chronic pain as an allegory.

EPPIC-Net’s mission is critical, we must learn how to sustainably bridge the gap between early drug development and the large clinical trials that ultimately lead to the approval of new pain medications. At the conclusion of one investigators’ meeting, then NIH director Francis Collins sang a folk song, “If not now tell me when.” One line in this song is: “Although there will be struggle we’ll make the change we can.” We make change by performing the research, but also by telling its story.

by PAIREDProject | May 12, 2023 | Autonomics, Pain

As neurologists, headache is one of the pain disorders we see most often, especially Dr. Mueller who is a headache specialist. Most patients with headache have episodic symptoms and go back to feeling normal between attacks. But some suffer from headaches almost every day, and even when they don’t have pain, they still don’t feel normal. There’s fatigue, brain fog, dizziness and other symptoms that their doctors don’t seem to understand.

Pain is a stressful experience, and the autonomic nervous system (ANS) orchestrates the stress response, including changes in blood pressure, heart rate, and alertness. But like any good conductor, a properly functioning ANS knows when to decrescendo. Perhaps as headaches become more frequent, and the ANS is repeatedly called to action, it begins to have trouble returning to a resting state. Could changes in the ANS cause the other non-painful but debilitating symptoms that can accompany chronic headache?

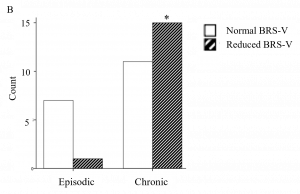

With Dr. Mueller in the lead, we studied 34 people with headache who had undergone autonomic testing in our lab, comparing those with chronic headache to those with episodic headache. The testing performed at the Mount Sinai autonomic lab has several parts as described by PAIRED Project alum, Alyha Benitez, in this video. We can use the results of our autonomic testing to describe autonomic function and dysfunction in different ways. One way is to calculate a summary score, called the Composite Autonomic Severity Score (CASS), which takes into account all the test results. We can also calculate other scores that look at individual parts of the ANS, for example BRS-V (which stands for vagal baroreflex sensitivity). BRS-V measures changes in heart rate in response to stress which is controlled by the very important autonomic nerve known as the vagus.

What did we find? Well, not surprisingly, people with chronic headache were far more likely to experience symptoms of fatigue, cognitive impairment and POTS. But let’s look at the results of the autonomic tests, which are summarized in the figure below.

The dark striped bars represent the number of people with reduced BRS-V. Among people with episodic headache (on the left), the dark striped bar is very low indicating that very few have abnormal BRS-V. But in people with chronic headache (on the right), the dark striped bar is much higher, indicating that more of them have abnormal BRS-V. We saw a similar pattern when we looked at the CASS score.

The presence of non-painful symptoms such as fatigue and cognitive impairment were also associated with autonomic dysfunction. The full results were published in Frontiers in Human Neuroscience in March. For more about headache and autonomic dysfunction also check out our review article in the journal Headache which has a cool figure describing overlapping mechanisms in POTS and migraine.

By Jessica Robinson-Papp, MD MS

By Jessica Robinson-Papp, MD MS

By Mary Catherine George, PhD

By Mary Catherine George, PhD Dr. George as the Countess in the Marriage of Figaro

Dr. George as the Countess in the Marriage of Figaro

Recent Comments