Working in teams

Team work and Collaboration

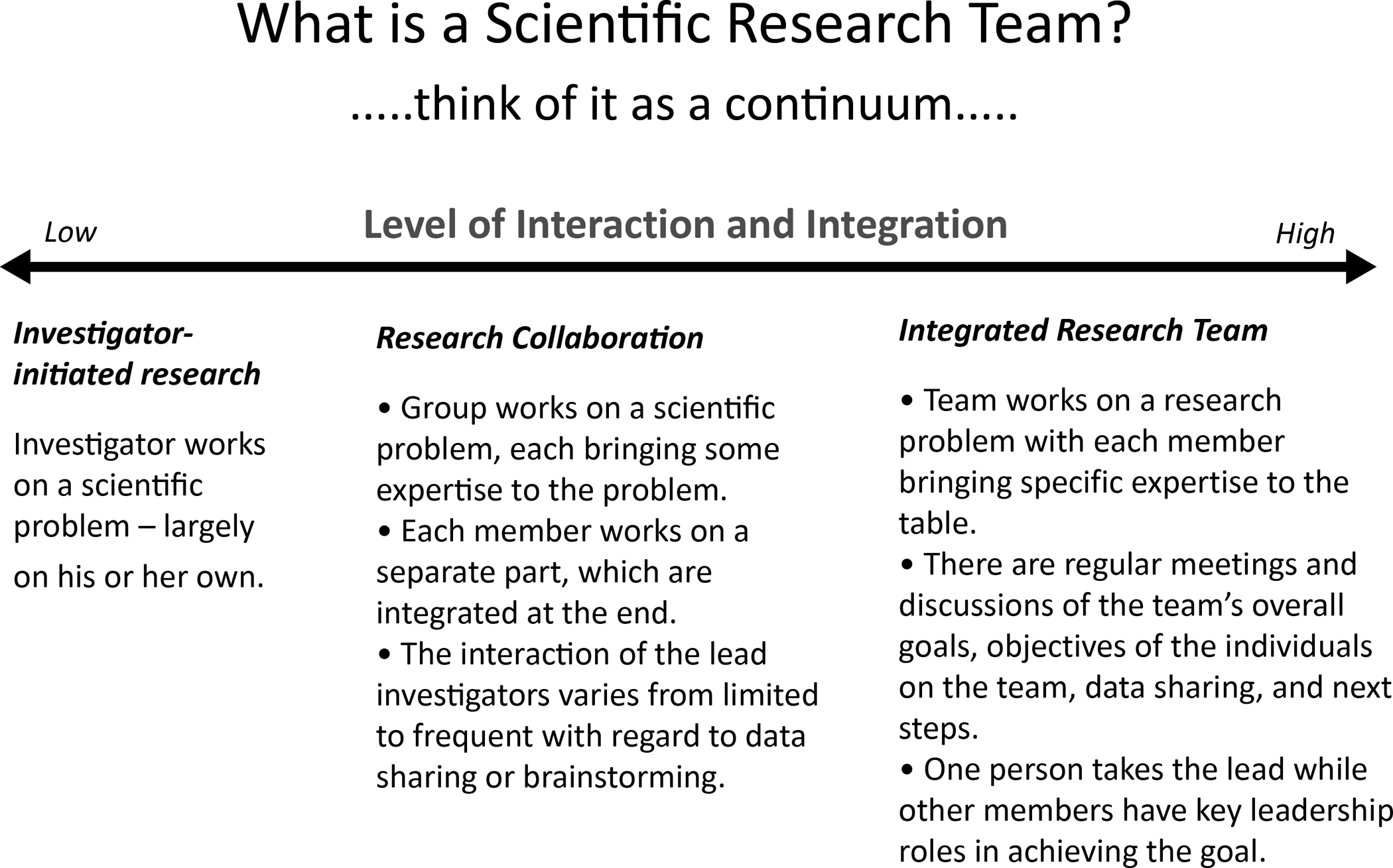

Research ventures where several researchers, groups or institutions work together to answer a research question is becoming known as team science. Bringing individuals together can often be helpful in tackling complex and important problems. Teams working together can produce better work because they take on more ambitious projects, bring complementary knowledge and apply diverse research methods. Teams also have larger social networks than individuals do, which helps to collect input during research and disseminate results as they emerge. In addition, in the best situations, teamwork promotes not only timely but also high-quality work, as people in the team have a strong incentive to demonstrate excellence to their partners.

Team science is not just good for science. As an emerging investigator, it gives you the opportunity to take part in research with high impact that would otherwise not be accessible. It can remove the pressure to obtain independent funding – in many cases, all funding will have been obtained as part of the larger project’s grant and offers the opportunity for all members to learn from each other. Diverse experiences and skills are clearly a benefit, but team members may also productively complement each other by balancing breadth versus depth, basic versus applied research directions and quantitative versus qualitative approaches.

Many teams report satisfaction and fun with teamwork, but not all teams have positive experiences. While mild disagreements are common and can even be productive, disruptive conflicts can undermine team performance. The opposite challenge is “groupthink”, where team members are too quick to accept ideas without sufficient exploration and discussion. Teams also face difficulties when team members don’t contribute evenly.

What makes a good team?

Evidence from across the literature suggests that successful teams have the following characteristics:

Balanced teams. Teams with members of the same discipline can be effective when they have complementary skills, but you should consider team members from nearby or even distant disciplines, who can bring fresh problems, research methods or analytic tools.

Previously successful collaborations. A strong correlate of team success is a history of successful previous collaborations. Successful collaborations call for establishing common ground — a shared vocabulary and compatible working styles — and building trust. To find out if you can be productive with a group start with a small collaboration before committing to a longer-term one.

Clearly defined goals and roles. As your team forms, you should write a shared vision of the overall goals and clarify individual roles, especially when working in large distributed teams. When authoring a proposal, report or paper, people’s specializations may emerge. For example, some people may be great at producing titles, abstracts and introductions, while others may do excellent reviews of previous work.

Explicit statements of who does what by when. You should also develop an initial schedule that allocates tasks to be accomplished with deadlines to be met. You can change it later, but having a clear specification of contributions from each team member is helpful — whether the plan is short-term work leading to a conference submission or a multiple-year endeavor to deliver major breakthroughs, working systems or mature products. This strategy requires outlining specific, concrete steps and timelines for completing them.

Regular and open discussion. Teams are best when they hold regular and open discussions. Groups in which a number of different people speak during meetings tend to perform better than teams in which one or two people dominate the discussion. Modest controversy is often healthy in choosing among alternative directions as well as in promoting trust among team members. Another commonly stated principle is that you should always be open to seemingly wild ideas that may offer unorthodox solutions or initiate new lines of thinking.

Good communication. Team members may have to learn how to speak to each other in constructive and positive ways during informal one-on-one discussions and in face-to-face group meetings. Often, getting team members to agree on terminology is a big step forward in forming common ground. Communication also includes respectful dialogue, so replacing “your idea just won’t work” with “I don’t understand why you want to do it that way” changes the atmosphere in the room, raising the willingness of team members to contribute and inviting productive differences of opinion. When team members rehearse talks within the team, they not only promote team cohesion but probably produce better presentations to outsiders. Simply describing your work to other team members helps to clarify your intentions.

Collaboration readiness. This occurs when team members are eager to work in the team and their management is supportive of team participation. Loners who are reluctant to work in teams are unlikely to become productive team members, and managers who fail to encourage teamwork may undermine the team by providing inadequate resources or disparaging team successes. Some institutions promote a culture of collaboration by training for teamwork, making collaboration technologies readily available and celebrating successful teams.

Technological readiness for remote teamwork. The reality of contemporary teamwork is that inevitably some members will be traveling, while others are embedded in distant organizations, making regular face-to-face meetings difficult. You should rely on technology to facilitate collaboration at a distance and help to bring team members closer together regularly to describe progress, share problems, exchange ideas and forge agreements about future plans. Meetings by phone, Skype or video conference can help groups of three to 30 to coordinate their activities, learn from each other and build trust. For larger groups, web conferencing tools like WebEx or GoToMeeting support presentations and discussions, while wikis, blogs and deliberation systems provide durable records of substantive discussions including documents, links, data sets, videos and more.

Trained experienced leadership. Great leaders set visionary goals, inspire younger team members, push for high quality and share the recognition and rewards. They also are attentive to and step in to resolve conflicts among team members, keep the project on schedule, deal well with setbacks, and even know when to remove someone from the team. In small teams, democratic management with no designated leader is possible, but as the size of your team grows, a strong leader will become an increasingly valuable asset.

Effective brainstorming strategies. Thousands of studies of brainstorming, usually in design and engineering, have shown that there are good and bad practices. While it can sometimes be helpful to have lively group discussions to develop new ideas, fresher and more diverse ideas emerge more reliably if individuals begin brainstorming on their own. Your team members should then meet to present their ideas in a safe, nonjudgmental process that allows for clarification, questions and refinements. Facilitated brainstorming sessions, with trained leaders, often elicit bold innovative ideas, which the team can discuss and refine.

Useful Resources for Finding and Working with Collaborators

- Collaboration and Team Science: From Theory to Practice

- How to Collaborate

- PLOS: Ten simple rules for cultivating open science and collaborative research & development

- Ten Rules for successful research collaboration

- ISEH: New Investigator Digest. Collaborative research: the why and how to collaborate in science.

- A brief guide to research collaborations for the young scholar