Mutational processes in cancer and normal cells

Mutation can happen in any cell in the body but only occasionally lead to cancer.

What processes initiate and propel the progression of cancer?

How do these processes predict clinical outcomes in cancer patients?

If not causing cancer how somatic mutations contribute to other diseases?

These are some of the questions we are interested in answering. Sequencing tumours show numerous mutations. I have shown that most of the somatic mutations that we detect in cancer happened in pre-cancerous cells and most likely did not contribute to cancer development. But these mutations, that we call passenger mutations, help us to develop early detection methods for cancer. And we use a machine learning approach that uses these mutations as input to identify cancer types without a need of a pathologist. We also use these genomic biomarkers to improve predictors in response to therapy than current approaches. And lastly, if most cells accumulate mutation we need to understand their role in common disease and aging.

Polak, Karlic, et al, Nature 2015

Kubler, Karlic,et al, biorxiv 2019

Lawrence*, Stojanov* Polak*, et al , Nature 2013

Polak et al, Nature Biotechnlogy 2014

Haradvala*, Polak*,Cell, 201

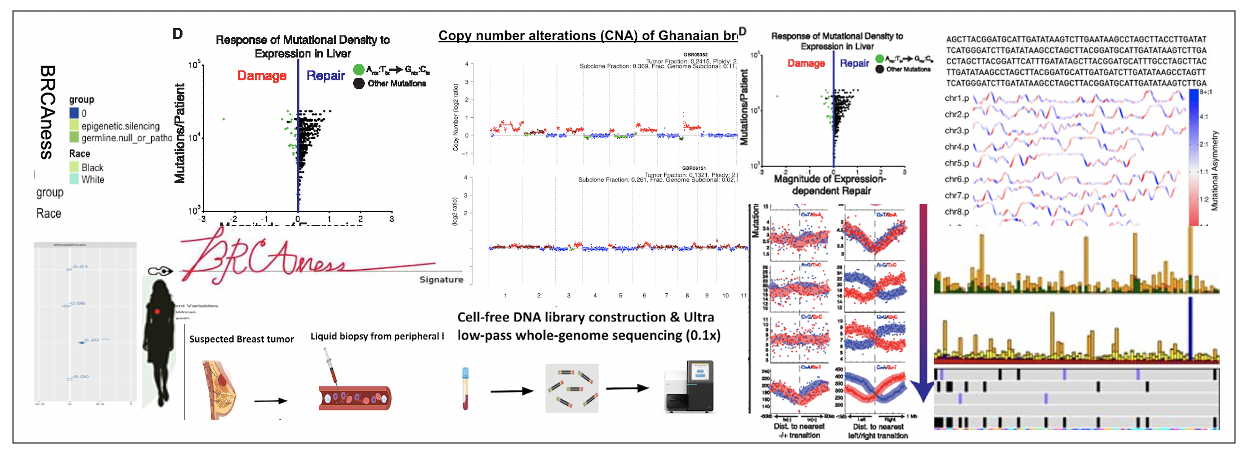

Ancestry and Cancer Genomics

The most aggressive breast cancer subtype, the triple-negative breast cancer (TNBC) subtype, is two times more common in black breast cancer patients compared to whites. Prostate cancer is the most common cancer man over at the highest rates in black men. The reasons are unclear. In the age of precision medicine when more and more drugs tailor to mutations most of our knowledge is based on the tumour from white patients. It is possible that patients from understudied populations will have mutations in genes that are not common in white patients.

Another complicity is that self-reported race is a social construct and does not capture the full ancestry picture of the person. To expand the benefits of the drugs conferred by genomic analysis, we infer the genomic ancestry from the DNA sequencing data. We assure that we capture the genomic diversity within patient populations. Doing so enables us to discover if the frequency of mutation in cancer driver genes is dependent on the ancestry fraction. Once we identify such genes, we design proper models to study the response of drugs to the mutation

Polak, Kim et al, Nature Genetics 2017

Koga et al, Clin Cancer Res 2020

Identify tumours with DNA repair defects

Mutations in DNA repair are common in some of the deadliest tumours: ovarian cancer triple-negative breast cancer pancreas and metastatic prostate cancer. New therapies are currently developed to target tumours who luck one of DNA repair pathways. PARP inhibitors (PARPi) are new drugs that are approved for patients with mutations in BRCA1/2 genes. However, by sequencing tumors, there are at least three times more patients than we predicted that can benefit from PARP inhibitors and most tumors do not harbour mutations in BRCA1/2 genes.

In the next years, we will use tumour sequencing data from 100K cancer patients to complete the identification of specific signatures of DNA repair genes. We will use these to increase germline and somatic panels.

Polak*, Kim*, Baruanstein* et al, Nature Genetics 2017

Kim* Mouw* Polak* et al, Nature Genetics 2016

Hughley, Karlic, Joshi, Turnbull, Foulkes, Polak, NEJM, 2020

Foulkes WD, Polak P. NEJM. 2020

Liquid biopsies for early detection of cancer in West Africa

West Africa is experiencing a rapid increase in cancer incidences which now surpasses mortality due to infectious diseases. A major problem is that cancer is detected too late when it has already progressed. We are developing an affordable blood test called cell-free DNA (cfDNA) sequencing in combination with computational biology algorithms that can detect and diagnose cancer in Ghana. This development is done with colleagues in Ghana and we hope this technology will transform the way cancer is managed in this part of the world.