OUR RESEARCH

Using multimodal neuroimaging (EEG, MRI), psychophysical testing, eye tracking, and targeted clinical assessments, our research investigates sensory and perceptual processing as they differ between autism spectrum disorder (ASD) and typical development. We also examine the convergence and divergence between ASD and other neurodevelopmental disorders, including schizophrenia, as well as relations between experimental effects and specific patterns of clinical symptoms within the broad ASD population and among individuals exhibiting known genetic mutations that contribute to an ASD phenotype.

Our work address the following central questions:

Question 1: Mechanisms of sensory and perceptual processing alterations in ASD

Sensory processing difficulties affect up to 90% of individuals with ASD. In fact, many families report that, on a day-to-day basis, they are among the most impairing parts of autism. And yet, sensory symptoms are diverse: different modalities (sight, hearing, touch) may be affected or unaffected, and individuals with ASD may be over-sensitive, under-sensitive, or have significant sensory cravings. From basic science, much is known about how sensory systems are organized in the brain and about what brain pathways, neurotransmitters, and interactions between populations of brain cells affect sensory functioning. This body of knowledge allows us to ask questions and uncover the brain-basis of sensory symptoms in ASD. Sensory systems are also among the first to develop in the brain and lay the foundation upon which more complex brain functions are built. In that sense, sensory processing differences may not only be important symptoms to understand in their own right, but may also give us clues to how social, communication, and behavioral differences in ASD develop.

Sensory processing difficulties affect up to 90% of individuals with ASD. In fact, many families report that, on a day-to-day basis, they are among the most impairing parts of autism. And yet, sensory symptoms are diverse: different modalities (sight, hearing, touch) may be affected or unaffected, and individuals with ASD may be over-sensitive, under-sensitive, or have significant sensory cravings. From basic science, much is known about how sensory systems are organized in the brain and about what brain pathways, neurotransmitters, and interactions between populations of brain cells affect sensory functioning. This body of knowledge allows us to ask questions and uncover the brain-basis of sensory symptoms in ASD. Sensory systems are also among the first to develop in the brain and lay the foundation upon which more complex brain functions are built. In that sense, sensory processing differences may not only be important symptoms to understand in their own right, but may also give us clues to how social, communication, and behavioral differences in ASD develop.Question 2: Overlap between ASD and schizophrenia

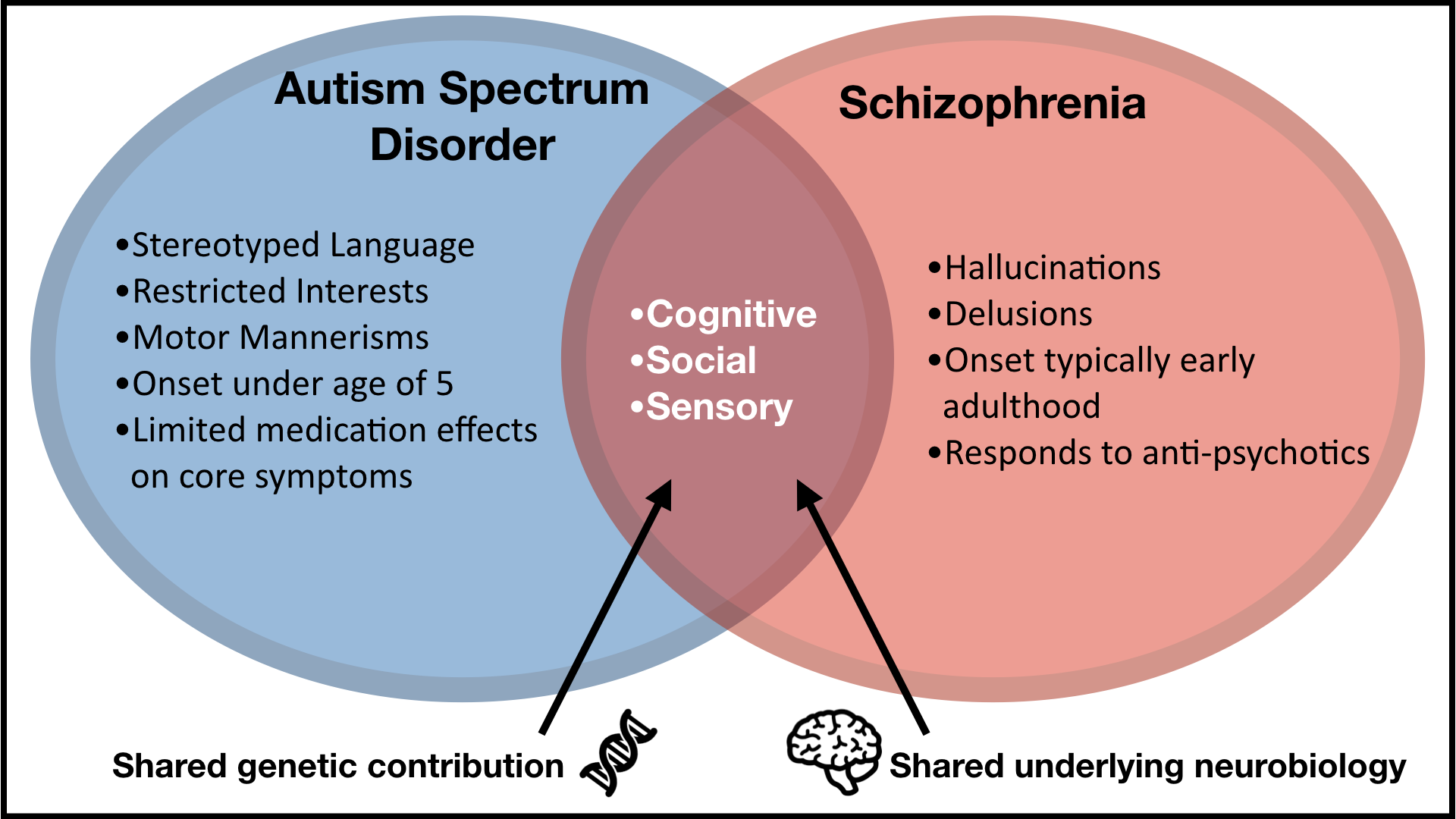

Autism and schizophrenia were once considered the same disorder. We now understand that there are many differences between the two and most people with ASD do not have schizophrenia or psychosis. However, research has repeatedly shown that there are genes and brain differences that ASD and schizophrenia have in common. Many symptoms, such as social difficulties and sensory processing differences, trouble both people with ASD and people with schizophrenia. Moreover, a small but important subset of children and adults with ASD will show psychosis symptoms. Clinicians will sometimes wonder whether these individuals may have both ASD and schizophrenia or psychosis at the same time, and right now there is still little research on the topic.

Autism and schizophrenia were once considered the same disorder. We now understand that there are many differences between the two and most people with ASD do not have schizophrenia or psychosis. However, research has repeatedly shown that there are genes and brain differences that ASD and schizophrenia have in common. Many symptoms, such as social difficulties and sensory processing differences, trouble both people with ASD and people with schizophrenia. Moreover, a small but important subset of children and adults with ASD will show psychosis symptoms. Clinicians will sometimes wonder whether these individuals may have both ASD and schizophrenia or psychosis at the same time, and right now there is still little research on the topic.Question 3: Genetics-first approach to understanding mechanisms and developing biomarkers for ASD

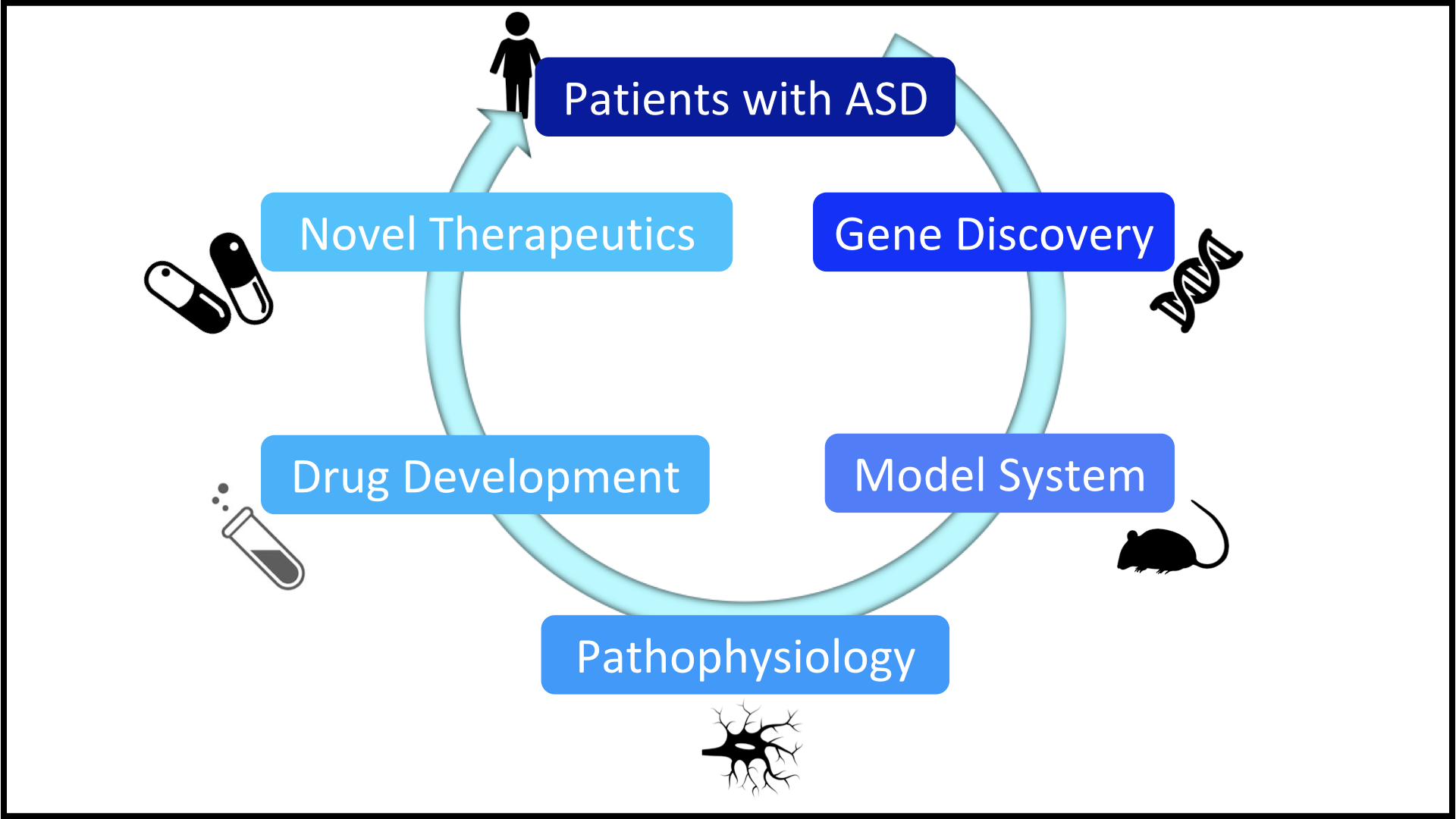

In the past decade, researchers have made large advances in understanding genes that contribute to autism. We now know of many specific genetic alterations (deletions, mutations, etc) that can confer high risk for ASD in affected individuals. Many of the genes that cause autism affect particular brain pathways, and basic science has told us much about the specific aspects of neurotransmitter, synapse, and cell structure and function that are directly impacted by these genetic alterations. Individuals sharing the same genetic alterations tend to have symptoms in common, making them a less heterogeneous group than we typically see in research and clinical work with individuals with ASD where the genetic origin is unknown. The Seaver Autism Center for Research and Treatment has an international reputation for its work in rare genetic syndromes associated with ASD, including Phelan McDermid syndrome, FOXP1 syndrome, and Fragile X syndrome. Our colleagues at Seaver are also conducting several clinical trials in these syndromes, which offers us the unique opportunity to explore how different interventions affect measurable aspects of brain functioning and behavior.

In the past decade, researchers have made large advances in understanding genes that contribute to autism. We now know of many specific genetic alterations (deletions, mutations, etc) that can confer high risk for ASD in affected individuals. Many of the genes that cause autism affect particular brain pathways, and basic science has told us much about the specific aspects of neurotransmitter, synapse, and cell structure and function that are directly impacted by these genetic alterations. Individuals sharing the same genetic alterations tend to have symptoms in common, making them a less heterogeneous group than we typically see in research and clinical work with individuals with ASD where the genetic origin is unknown. The Seaver Autism Center for Research and Treatment has an international reputation for its work in rare genetic syndromes associated with ASD, including Phelan McDermid syndrome, FOXP1 syndrome, and Fragile X syndrome. Our colleagues at Seaver are also conducting several clinical trials in these syndromes, which offers us the unique opportunity to explore how different interventions affect measurable aspects of brain functioning and behavior.In this line of research, we collaborate with colleagues at Seaver to explore several research avenues. First, how is brain functioning and behavior different in individuals with genetic disorders? How is sensory functioning impacted, and how do social and attentional symptoms present? Second, how do differences in brain functioning in those with genetic syndromes compare to those in individuals with ASD with unknown cause (“idiopathic ASD”)? Are there groups of individuals with idiopathic ASD whose behavior and brain functioning looks similar to that associated with a specific genetic disorder? If so, might this give us clues into neural alterations that are affecting a broader portion of individuals with ASD, even when we don’t know the specific cause? Third, can we develop biomarkers for ASD starting in genetic syndromes? Are there brain-based alterations that are reliable across time and individuals and that can easily be measured regardless of a child’s functioning level or the research or clinical setting? Do these markers help us know which children will benefit from a specific treatment? When we do treat children, do these biomarkers show change? Can this work inform biomarkers and treatment approaches for ASD more broadly?